Turning the Page on 2022

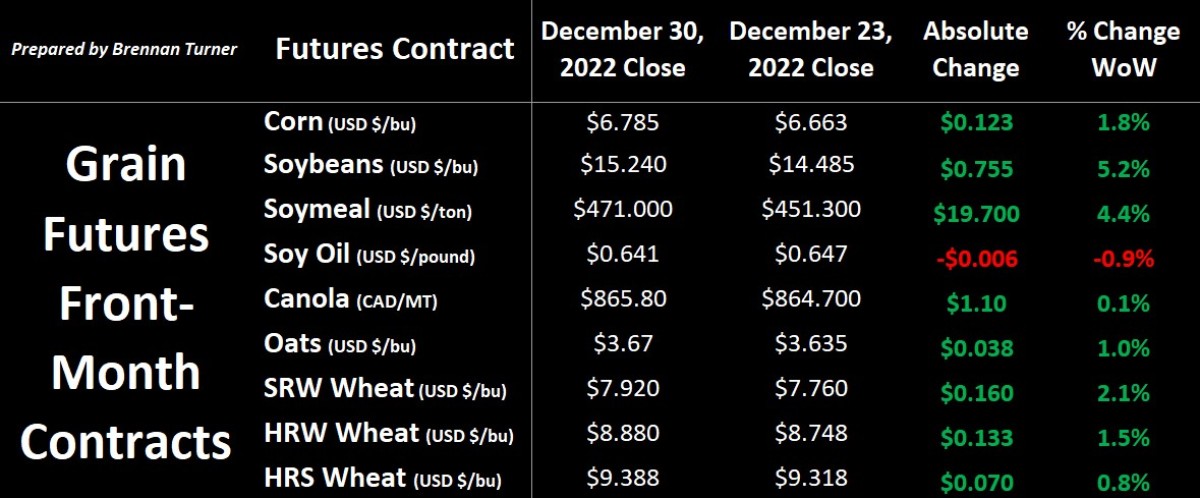

While most of us were tinkering with Christmas toys and slurping the last of the soon-to-be-expired eggnog, grain markets had a green finish in its last week of trading in 2022. The complex was led by soybeans, which is earning a weather rally thanks to the dry conditions in Argentina and southern Brazil. A late-December cold snap throughout North America supported wheat futures, but any ideas of significant winterkill (and bullish sentiment) was offset by expectations of the La Nina conditions relaxing by spring, and technical resistance in Kansas City HRW wheat at $9 and in Minneapolis HRS wheat at $9.50. On that note, corn speculators got more long this past week, after being the least bullish since September 2020, the week before.

Before reflecting on 2022’s grain markets and flipping the calendar into 2023, weather continues to be the most discussed variable. As it stands right now, the market is expecting more average conditions come March, but cold weather is expected for the first two months of the Year of the Hare (as per the Chinese calendar). While conditions may improve in North America, it continues to be dry in significant areas of South America, and since Argentina is the world’s largest exporter of soy oil and soymeal, the spillover impact to canola and feed grains is a real possibility.

Another major variable I’m watching is an acceleration of Russian wheat exports. As per SovEcon last week, Russia was set to export 4.1 MMT of wheat in December, a very healthy number considering the record for the 12th month of the year is 4.3 MMT (set in December 2017)! Speaking of records, there was still an estimated 25.6 MMT of wheat sitting on Russian farms at the beginning of December, a new all-time high and nearly 80% above the average. Coincidentally, with the Russian Ruble hitting its highest level against the US Dollar since April 2022, expectations are that Russian wheat exports will continue to cruise over the next few months (and especially since SovEcon is reporting that “current traders’ margins are great").

Obviously though, Russia had one of the greatest impacts on grain markets in 2022 after its military invasion of Ukraine in late February. Wheat and corn markets went parabolic for the subsequent two weeks as all of the unknowns and uncertainties of Ukrainian grain production and export flows were sorted out. But the damage was done with bullish sentiment quickly fueling a demand rally, which was amplified after the lower production totals of Harvest 2021. As a result, corn and soybeans futures traded at their highest levels since 2012 and Chicago wheat hit an all-time high and while we’ve certainly come down from those levels – especially over the last calendar quarter, as per the first table below – grain futures are still ending 2022 much better than where they were a year ago!

Puzzlingly, 2023 new crop grain futures aren’t all that different than where 2022 new crop futures were priced at this time a year ago. Yes, it’s important to keep in mind that Putin hadn’t tried to take over Ukraine yet, but the market was basically telling us that it was willing to pay a premium to secure new crop supplies. This was especially true if it was a crop negatively impacted by the drought-riddled yields of the disappointing Harvest 2021 (see canola, HRS, and oats on the tables above and below for spot and new crop values, respectively).

While we certainly were able to see a return to average yields this past harvest, buyers have had to play musical chairs because of the Ukrainian grain export disruption, adding some demand premium to the markets (and therefore, ongoing tight balance sheets). Therein, with limited carryover into the 2023/2024 crop year (relatively speaking), grain markets are at a price equilibrium that reflects more or less a similar sentiment as what we were in last year.

Thus, grain prices are likely to stay elevated in the first half of 2023, or at least until we know what production potential looks like. This will be especially true for the current South American soybean and corn crops, and the U.S. winter wheat crop, albeit, as I mentioned at the beginning of December, production concerns don’t really tend to show up in the winter wheat market until the mid-to-late spring. We’ll look at this in more detail next week, as well as how cash markets perform the in the second half of the crop year.

To growth,

Brenna Turner

Founder | Combyne Ag